Today’s topic is Algorithmic complexity for #geospatial people.

Or what the heck is Big O any way.

If you’ve been around programmers for any length of time you’ve probably heard of Big O. (settle down nsfw folk, this is about algorithms and programming not that)

The short version is its a way of describing the worst case runtime of an algorithm with regards to the amount of data. Given n bits of information what’s the order of magnitude of the worst possible run time. O(n)? O(n^2)?

Say we have a set of latitude and longitude points. We need to convert them to a different coordinate system. This requires us to visit every point and do the transformation function.

It doesn’t matter how many points there are we have to visit each one once. So this is described as O(n) this is linear, the more points we have the longer it takes, but doing 10000 takes 10 times longer than doing 1000, and 1000 takes 10 times more than 100 etc.

It also is explicitly always the worst case runtime. So if you have an algorithm that is finding the the first point in a cloud inside an area, it can stop and exit as soon as it finds one, but if none of the points are inside the area then it will have to check every point. So while on average it would be n/2 comparisons you would always have a big O notation of O(n)

If we have to find the pair of those points furthest away from each other. We could write some code that goes through each point and then calculates the distance to every other point to find the longest distance.

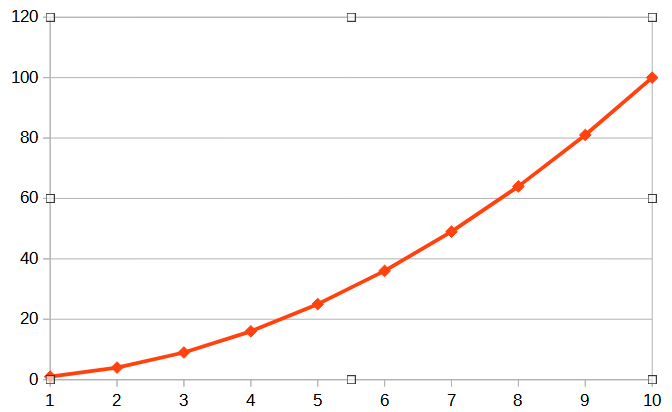

The version of this where you check every point every time would require O(n*n) operations or O(n^2) the more points you have the worse things get in a big way.

But we can improve this algorithm significantly, the distance between points doesn’t change depending on which way round you compare them. So we don’t need to check every point every time, we can skip the ones we’ve already done. However this only makes it O(n*(n-1)/2) One of the quirks of Big O notation is that you always get rid of any numbers or fixed terms and simplify the expression down to only the largest terms to give a rough order of the problem. So even the improved version is O(n^2)

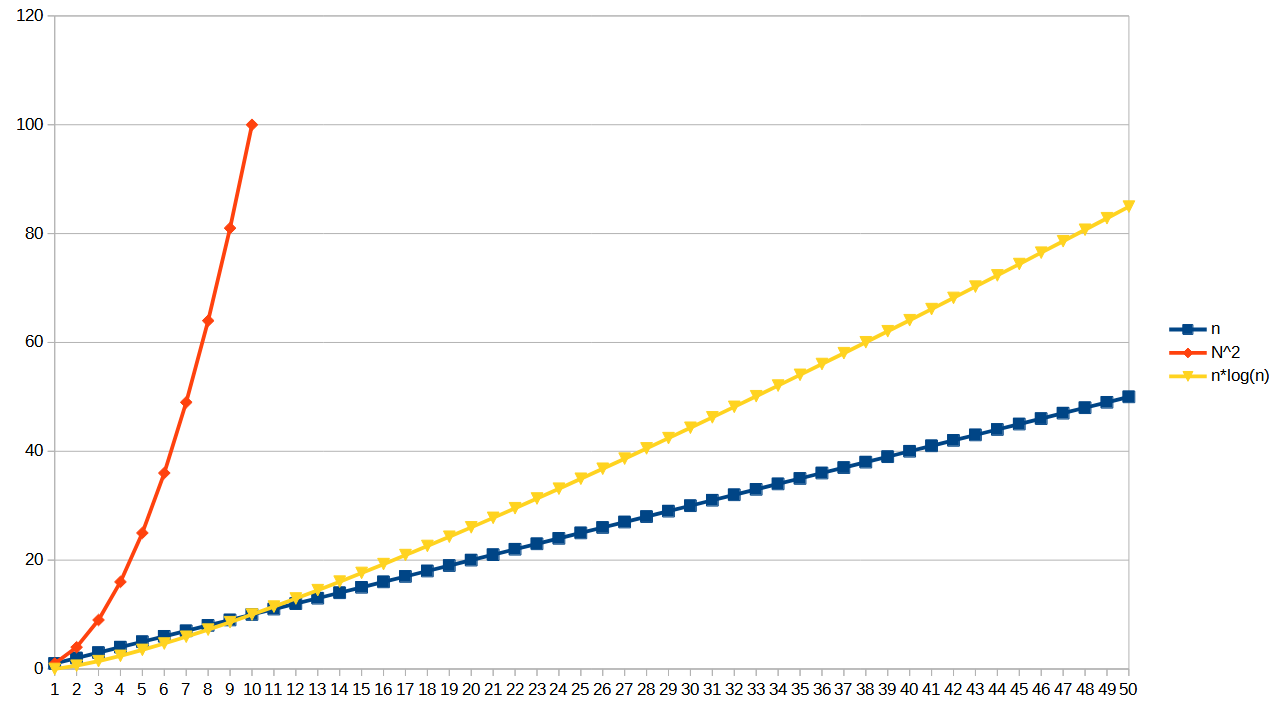

Another common order is O(n*log(n), this is often seen in recursive merge algorithms, and things that take divide and conquer approaches. The graph below shows nicely how this is better than O(n^2) but not as good as O(n)

The idea of Big O notation is to allow you to compare different approaches to problems at a high level and what your scaling difficulties are going to be. An O(n^2) solution might be fine, if you know that n is only ever going to be a small number. The point is to have the tools to describe this kind of thing to each other.

With thanks to @adamb@aus.social for pointing out an error with this post.